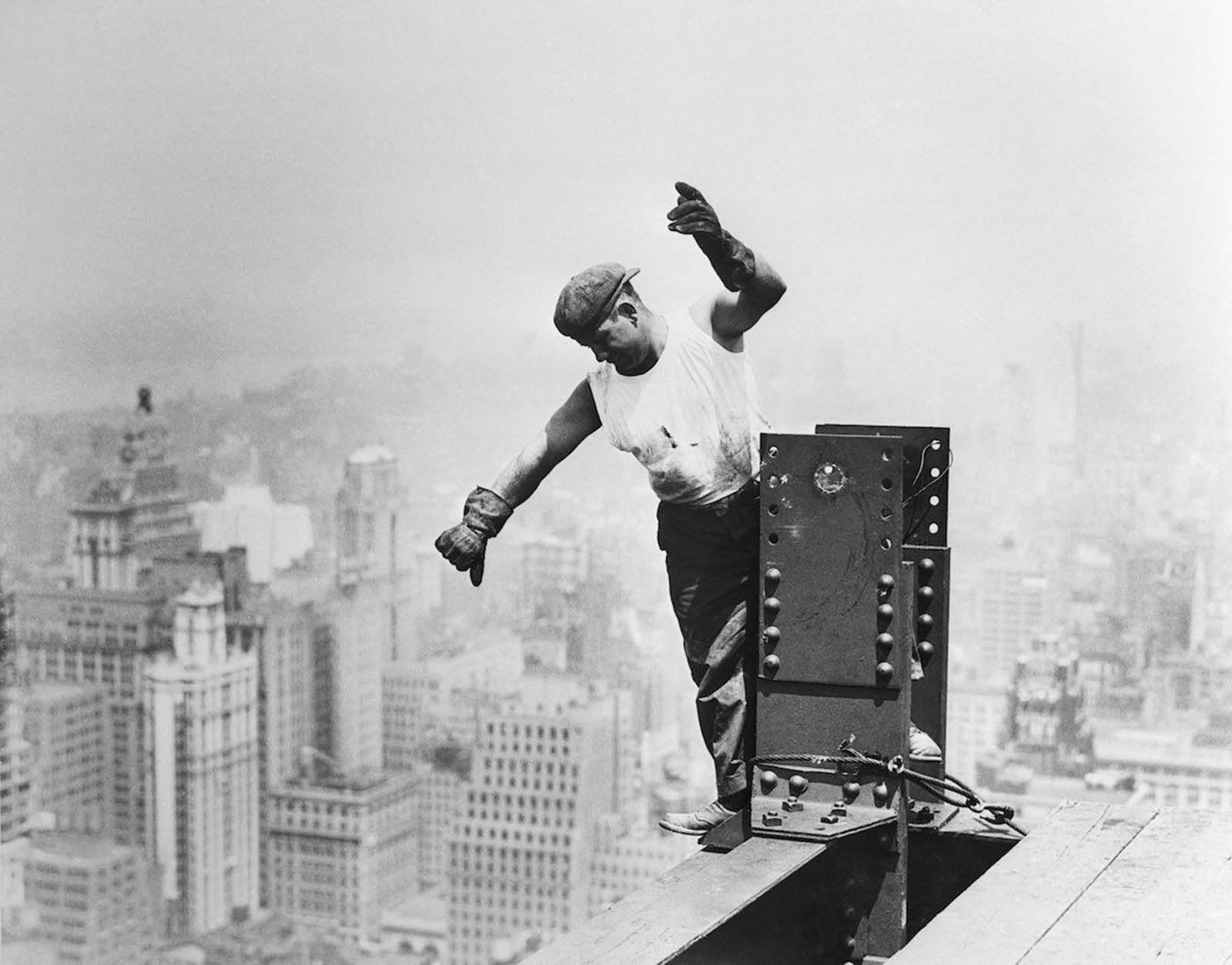

The only thing as impressive as the Empire State Building are the men who built it and during that time rules for construction workers were a lot laxer than they are today. The hardworking men way up high who were moving girders, riveting, painting, and even just eating lunch or resting earned a reputation for being daredevils.

They worked with minimal harnesses (sometimes without any), walked nonchalantly along beams suspended hundreds of feet above the street, swung on cables, sometimes they even took short naps on the metallic beams. The Empire State’s construction work and its workers were a magnet for press and magazine photographers, which is how many of these iconic images of the construction work were created.

The gravity-defying ironworkers balanced on narrow beams or hung from derrick lines hundreds, and even thousands, of feet above the city’s streets.

The New York Times wrote that they “put on the best open-air show in town. They rode into the air on top of a steel beam that they maneuvered into place as a crosspiece by hanging to the cable rope and steering the beam with their feet, then strolling on the thin edge of nothingness.”

“Air like wine. An unusual picture of one of the intrepid window washers working on the Empire State Building, as he pauses in his task to draw a lung-full of clean air at his height. With the oncoming of the warmer weather our skyscrapers begin to look like giant ant-hills as these washers clamber over the faces of the structures calmly doing their nerve-tingling work. Or maybe the fellow pictured here is just issuing an invitation to the cameraman to come a little closer.”

Along with the steelworkers were the intrepid teams of riveters, who drove red-hot rivets into the beams, fastening them into place to create the building’s steel skeleton.

London’s Daily Mail compared the workers to classical heroes: “They were right there, in the flesh, outwardly prosaic, incredibly nonchalant, crawling, climbing, walking, swinging, swooping on gigantic steel frames.”

As fearless as the riveters and ironworkers seemed, there was one danger they heeded: weather. When it rained, there was a danger of slipping; when it was bitterly cold, stiff, or numb hands could not hold onto anything.

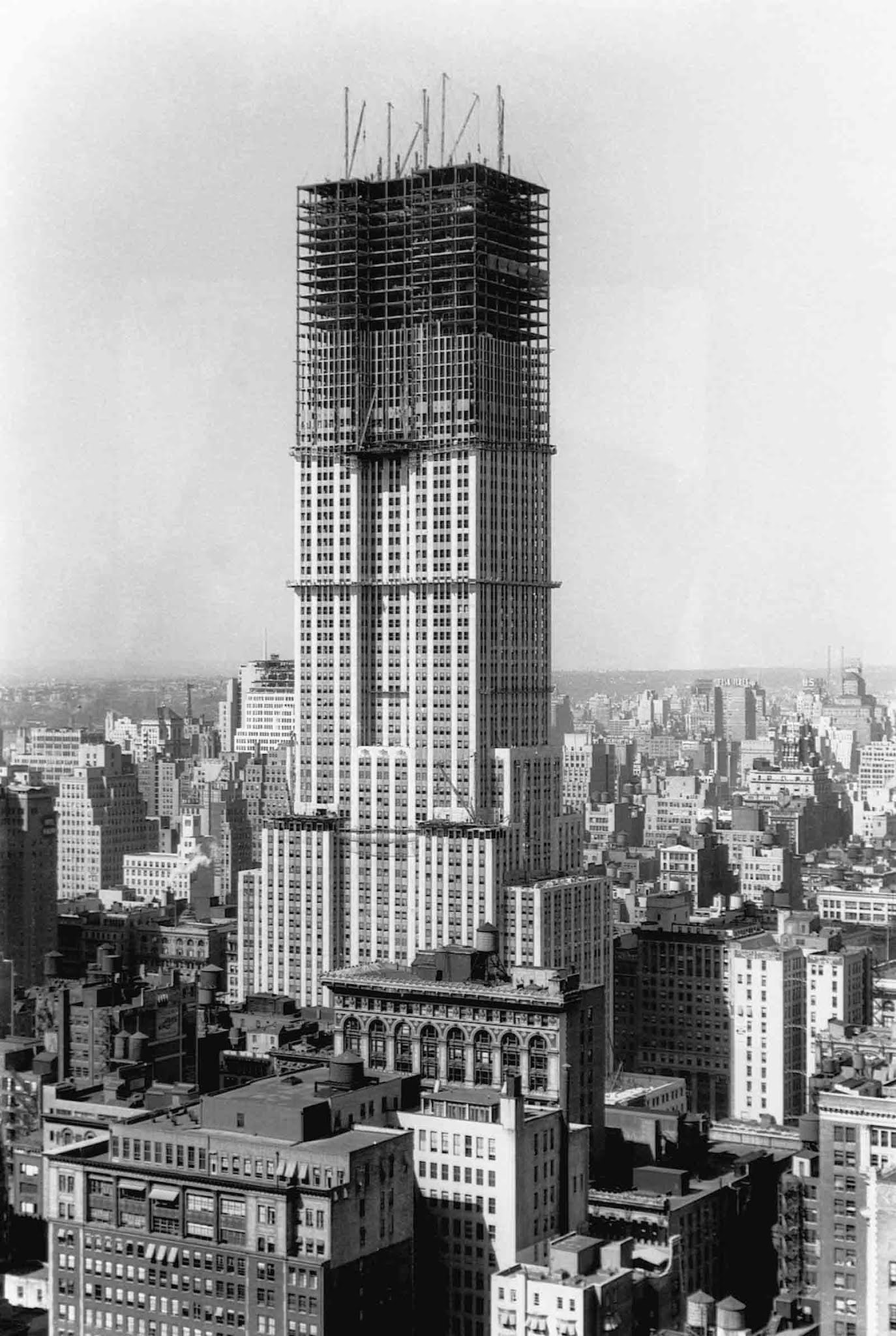

Empire State Building, steel-framed skyscraper rising 102 stories that was completed in New York City in 1931 and was the tallest building in the world until 1972 when it was surpassed by the World Trade Center building.

The project involved more than 3,500 workers at its peak, including 3,439 on a single day, August 14, 1930. Many of the workers were Irish and Italian immigrants, with a sizable minority of Mohawk ironworkers from the Kahnawake reserve near Montreal.

According to official accounts, five workers died during the construction, although the New York Daily News gave reports of 14 deaths and a headline in the socialist magazine The New Masses spread unfounded rumors of up to 42 deaths.

“Carl Russell waves to his co-workers on the structural work of the 88th floor of the new Empire State Building. When complete the highest man-made structure in the world will rise 1,222 feet above the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street. The cameraman risked his life climbing a derrick to snap this unusual photograph. Notice the “Toy” cars and the ant-sized pedestrians walking about Herald Square almost a quarter of a mile below.”

The Empire State Building cost $40,948,900 to build, including demolition of the Waldorf–Astoria (equivalent to $564,491,900 in 2019). This was lower than the $60 million budgeted for construction.

The Empire State Building officially opened on May 1, 1931, forty-five days ahead of its projected opening date, and eighteen months from the start of construction. The opening was marked with an event featuring United States President Herbert Hoover, who turned on the building’s lights with the ceremonial button push from Washington, D.C.

According to The New York Times, builders and real estate speculators predicted that the 1,250-foot-tall (380 m) Empire State Building would be the world’s tallest building “for many years”, thus ending the great New York City skyscraper rivalry.

At the time, most engineers agreed that it would be difficult to build a building taller than 1,200 feet (370 m), even with the hardy Manhattan bedrock as a foundation. Technically, it was believed possible to build a tower of up to 2,000 feet (610 m), but it was deemed uneconomical to do so, especially during the Great Depression.

“Empire State Building under Construction”

As the tallest building in the world, at that time, and the first one to exceed 100 floors, the Empire State Building became an icon of the city and, ultimately, of the nation.

The Empire State Building only started becoming profitable in the 1950s, when it was finally able to break even for the first time. At the time, mass transit options in the building’s vicinity were limited compared to the present day. Despite this challenge, the Empire State Building began to attract renters due to its reputation.

A 222-foot (68 m) radio antenna was erected on top of the towers starting in 1950, allowing the area’s television stations to be broadcast from the building.

“A ‘blimp’ flying over the Empire State Building.”

“It may be painful for the ant-like spectators in the street below, but it’s all in a day’s work for these smiling window washers as they go about their precarious work cleaning up the Empire State Building, world’s tallest structure, at dizzy heights of hundreds of feet above the street.”

“The startling ‘shot’ was made by the photographer looking down upon the window washers on the 34th street side of the world-famed building. Note the tiny insects that are motor cars and pedestrians.”

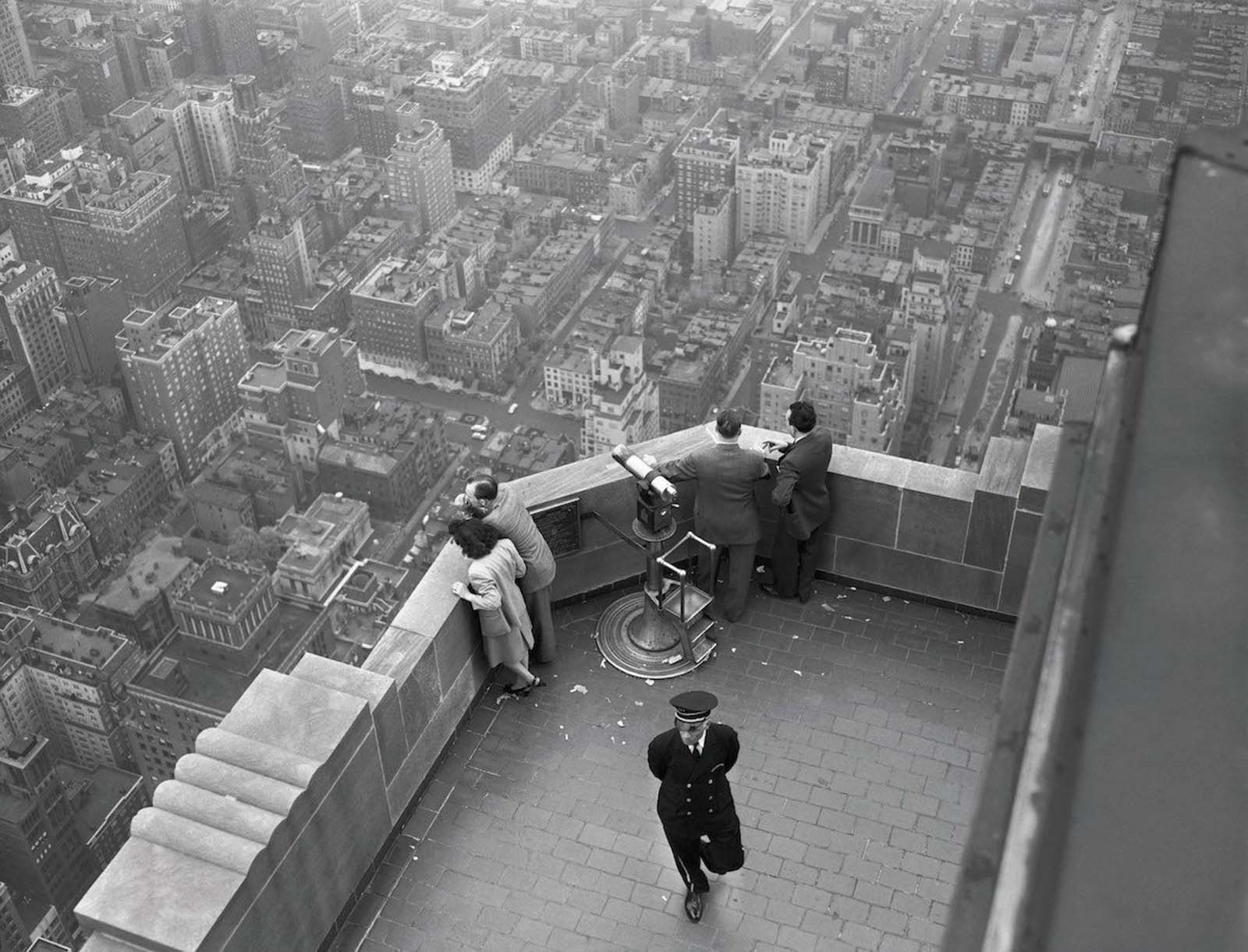

“Aerial view of New York City atop the Empire State Building”

“Flirting with danger is just routine work for the steel workers arranging the steel frame for the Empire State Building, which will be the world’s tallest structure when completed.”

“New York City: Lighting Up ‘Way Up.’ A striking silhouette atop the gigantic RCA Building in Rockefeller Center, New York, as workmen light their cigarettes at the end of a working day. The Empire State Building rises dramatically in the background.”

“Erected on the site of the old Waldorf Astoria, this building will rise 1,284 feet into the air. A zeppelin mooring mast will cap this engineering feat.”

“An odd photographic trick placed this steelworker’s finger on the lofty pinnacle of the Chrysler Building. This view was taken from the Empire State Building, the world’s tallest building, which is now rising on the site of the old Waldorf-Astoria in New York City. A mooring mast for dirigibles will cap this 1,284-foot structure.”

“A construction worker hangs from an industrial crane during the construction of the Empire State Building.”

“Ex-Governor Alfred E. Smith, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, and others at the top of the Empire State Building, tallest in the world, gazing out over the New York panorama. This scene took place immediately after the official opening of the structure this morning, which was completed when President Herbert Hoover pressed a telegraph key back in Washington, DC, which turned on all of the building’s lights. Mr. Smith is the president of the company that built the building.”

“Workmen at the new Empire State building that is being erected on the site of the old Waldorf Astoria Hotel at 34th Street and 5th Avenue. in New York, by a corporation headed by the former Governor Al Smith, raised a flag on the 88th story of the great building, 1,048 feet above the street. The flag thus is at the highest point in the city higher than the Chrysler Building. Photo shows the workmen at the ceremonies.”

“Workmen place one of the new beacon lights in position on the 90th floor of an impressive electronic crown in the form of four far-reaching night beacons. Combined, the four Empire State Night lights will generate almost two billion candle power of light and will be the brightest continuous source of man-made light in the world. Engineers say the beacons can be seen from as far as 300 miles. The cost of the installation is $250,000.” 1956.

“View From the Top of the Empire State Building”. 1947.

(Photo credit: Libary of Congress / National Archives / Bettmann / Corbis / Walks of New York).